Tourists takes tourist photos which are limited, inevitably, to shots of features—mountains, shores, bays, sunsets, waterfalls, architecture, the list seems endless—to which they are attracted because they aren’t accustomed to them in their familiar environments. What they see are only the most salient features of where they are, often made so by commercialization. One must inhabit a landscape over time, perhaps for a lifetime, if one is to photograph its true character.

I have lived along the south shore of lake Erie for forty years, the last twenty in an inner ring suburb of Cleveland that abuts the Cleveland Metroparks Rocky River reservation. From my back yard I can step down to Coe Creek and follow its soggy path for a quarter mile to the river itself. This is the reality with which I am familiar.

The Rocky River reservation runs for thirteen miles through layers of clay, shale and gray sandstone from the river’s mouth in lake Erie to a tumbling water fall in Berea, Ohio. Beyond that, the park becomes the Mill Stream Run reservation, another part of the countywide parks system locals call the Emerald Necklace. The level of the river changes dramatically because of late winter thaws, soaking spring rains and summer thunderstorms. But in all seasons, if one is patient, it is possible to walk those thirteen miles in the river itself. When the river is high, bridle paths and hiking trails too numerous to count along the riverbanks offer alternative routes through the dense deciduous forest. The Rocky River, my home, is a photographer’s paradise.

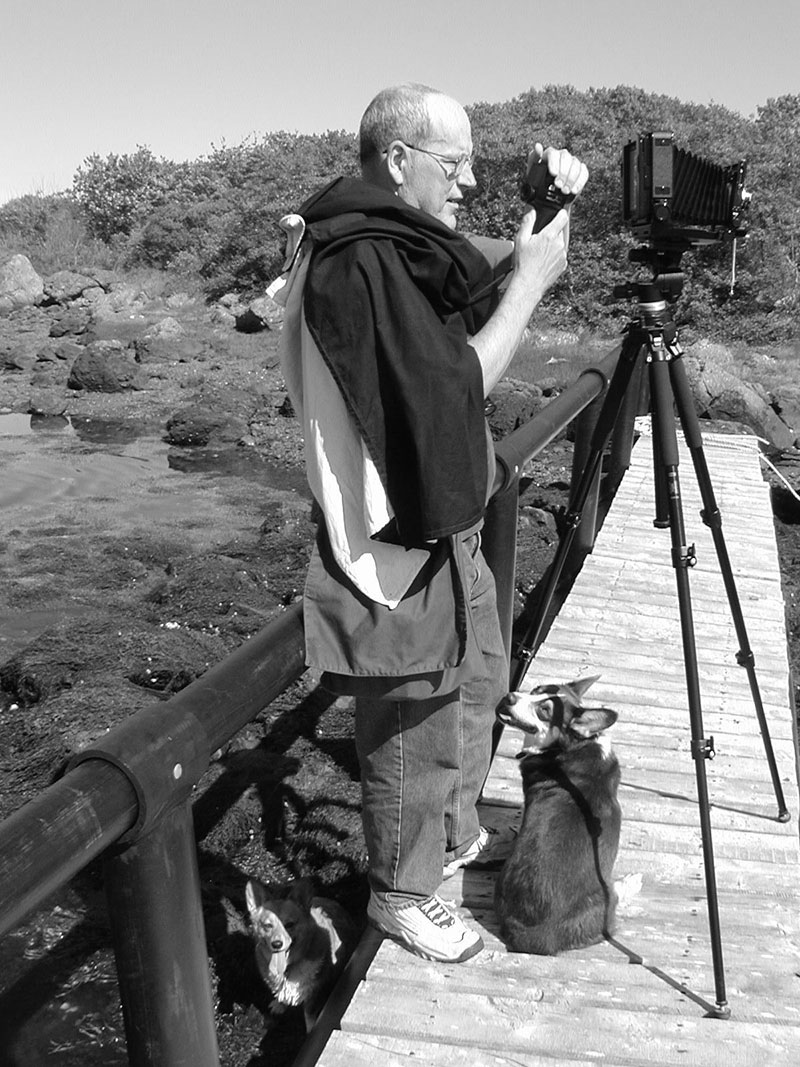

Over the years, I have covered these thirteen miles in small increments more times than I can remember. A typical excursion for me is a three or four hour walk actually in or beside the river during which I may take five or six shots. Early on I carried a Toyo 4×5, then graduated to a vintage Deardorff 8×10. Camera, tripod, film carriers and lenses together weigh forty pounds or more, so I carry an Amish oak cattle prod as a walking staff to help with balance in the rough terrain. In the beginning I walked in the morning on the unquestioned assumption that morning light is the most flattering. Ten years later, it occurred to me to walk in the afternoon and I saw for the first time an entirely different landscape. Around the summer solstice when light is most abundant, I walk at midday when the cover is thickest, the shadows deepest, and the effects most dramatic.

High water in the river is a light caramel color, heavy with silt. It reflects nothing of the sky but clears quickly as the level falls. Then it becomes what Thoreau, in Walden, calls skywater. Low water is ge nerally a pale yellowish green and so transparent that sluggish carp and weary steelhead are perfectly visible in the pools and currents. The bed is variously gravel, tumbled boulders, fractured sandstone, or delicate mosaics of shale. In season, algae soften the contours of the riverbed. And then, of course, there is the long season of ice, from sheets as fine as mica to great slabs riding up the backs of other great slabs in the current at the river’s mouth.

nerally a pale yellowish green and so transparent that sluggish carp and weary steelhead are perfectly visible in the pools and currents. The bed is variously gravel, tumbled boulders, fractured sandstone, or delicate mosaics of shale. In season, algae soften the contours of the riverbed. And then, of course, there is the long season of ice, from sheets as fine as mica to great slabs riding up the backs of other great slabs in the current at the river’s mouth.

It is never easy walking. When tired, I can find a fallen tree to sit on. They are everywhere in the woods. If one sits quietly enough, one begins to notice a dying tree teems with life. Both flora and fauna congregate there, from the tiniest insects transforming the wood into a spongy hummus, to the white tale deer that browse on the wild flowers springing from the moss underfoot. A fallen tree is the scene of a feeding frenzy—fungus, insects, worms, birds, snakes, voles, mice, squirrels, raptors, all dining in succession on the tree and each other. And that’s just during the day. Raccoon, opossum and coyote scat shows the feasting continues unabated at night.

I often wonder how much of this anyone really sees. Most people who pass through this environment seem to have an agenda: taking a short cut to the freeway, monitoring their calorie burn, improving their split times as they train for a marathon. The majority of tourists to Cleveland don’t see this landscape at all, unless it is through the tiny window of a plane landing at Hopkins International. They are much more likely to ride the rapid downtown, take a photograph of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to show their friends and family at home. “Look,” they might say. “This is what I saw in Cleveland.”

“Toward the Light” is my portfolio of the Rocky River. It is what someone familiar with Cleveland sees.

Category: cleveland

Toward the Light is my experience exploring the distinctive qualities of light in Cleveland, Ohio, where I live.

I know very little about the physics of light, and I am a self-trained photographer, so I can’t speak technically about it. But in my experience Cleveland light has its own character perhaps shared somewhat with other parts of the Great Lakes region.

It may have something to do with the latitude, though I doubt it, because the light in San Francisco, where I spend part of my year, is also of the same latitude but seems sharper.

I suspect it has to do with the humidity caused by lake Erie. The evaporation over the lake and drifting condensation over the land produce what locals know as a Cleveland sky, dense and lowering in the winter, high and soft and sculptural in the summer—a sky unseen anywhere else I have traveled. The resulting environment is a narrow rain forest along the lakeshore that fades away into the drier climate of central Ohio. Near the lake, the lambency of a humid August morning bathes the air with a light that rises from the ground, and Spring fog swaddles new foliage with a pale florescent glow as it floats in the air. Throughout the seasons, Cleveland light is always soft and forgiving.

Apart from the lake, there is so much water in the Cleveland environment—puddles, ponds, streams, rivers, marshes–that light is always rising from reflective sources to surprise the eye as it moves through the landscape. Even in deep woods, trees can be momentarily foot-lighted by pools of stagnant water as beams of passing light shoot through gaps in the foliage overhead.

What light falls on or passes through has much to do with how the quality of light expresses itself. Forest City was Cleveland’s original name and remains its nickname today, a testament to the density and extent of woods that cover the sinuous moraines deposited by the glaciers that formed the Great Lakes. It is possible, of course, thanks to architecture and agriculture, to escapes the woods and gaze directly at the sky, but the characteristic Cleveland experience—urban, suburban, exurban and rural—is still the walk under foliage or, in winter, its vast skeletal framework.

One thing I’ve learned photographing Cleveland is that leaves are always translucent. They can be almost opaque when plump with moisture and green with chlorophyll, but by Fall they have become thin, veiny, even lacy with only their ribs impeding the passage of light. The vast majority of Cleveland’s trees are deciduous, and the variety is unrivaled, meaning the shapes and colors of leaves seem infinitely varied. And the colors are in constant change, from the first lime-green buds of April to the last tan oak leaves clinging to bare limbs in January. Every variety has its distinctive palette throughout the seasons, so Cleveland autumn displays are distinct, if not for their brightness at least for their range of color. Light is constantly being filtered and colored by foliage through most of the year. And if that isn’t enough variety, the foliage, for the most part, is in steady, delicate motion. To the black and white photographer, this means the tonal range in a landscape can be so subtle that edges often blur.

Whatever the reasons, the light in Cleveland is alive, and the eye must be fully present to witness it.

obsessive emulsion disorder

The photo abstractions in the on-going series I like to call Obsessive Emulsion Disorder are made without using a camera. I expose black and white sheet film to a bare light bulb to produce a solid black negative in which all possible visual information (in the form of silver halide grains) is present. The black negative is a metaphor of chaos, but within that chaos is the potential for an infinite array of meaningful patterns waiting to reveal itself.

This revelation is accomplished by soaking the black negative in water, which slowly dissolves the colloid. This releases the silver, which can re-arrange itself free of any ego intent. The silver migrates on the film plane, slumping and thickening, or spreading and thinning. Different degrees of viscosity in the colloid influence how the silver  halide moves and how thick or thin it becomes. I can intervene at this point to influence the movement, but seldom do. My only tools for assisting the migration of the silver are a drinking straw to blow on the negative and an eyedropper for filling in abandoned space.

halide moves and how thick or thin it becomes. I can intervene at this point to influence the movement, but seldom do. My only tools for assisting the migration of the silver are a drinking straw to blow on the negative and an eyedropper for filling in abandoned space.

The next step is to reverse the process by drying the negative through evaporation, which hardens the colloid and fixes in place the redistributed silver halide. This often introduces fracturing, granulation and crystalization into the process. Most negatives are finished in two to three weeks. The longest I have spent on a single negative is 179 days.

The photographic enlargements resulting from these negatives are non-documentary images with the precision, detail, and tonal range of traditional documentary photography but with no documentary connection to the world. They do not and cannot represent perceptions or preconceptions by the artist. The images emerge from somewhere other than the artist’s ego, specifically from the chaotic potential of the film emulsion itself, though the darkroom artist is a necessary catalyst in the process.

I began using 4 x 5 negatives but have moved to 8 x 10, which I often scan and print digitally because I find imagery in sections of the negative (2 x 2 or less) too small to print with an enlarger.

My experience creating Obsessive Emulsion Disorder has convinced me there is no way to predict the outcome of this process, so when my ego tries to exert control it fails. Every image contains an element of surprise. When the result holds my attention over a sustained period of time, I feel I have achieved something spiritual—a heightened awareness of aspects of reality previously unseen.

The series Obsessive Emulsion Disorder received an Ohio Arts Council Award for individual excellence in photography.

I do not consider myself a documentary photographer because I do not believe photography has a documentary imperative. From a spiritual perspective, to grasp at life in order to create some sort of permanence is a misperception of reality, so to believe the camera preserves a moment in time is to believe photography perpetuates a delusion. Life is a process of perpetual becoming, of infinite creation. Life is art, and the meaning of art is the process itself: from inspiration, through creation to perception by another. This is the meaningful narrative arc repeated endlessly through the illusion of time. Photography can only tell the truth if it affirms this.

So if I am not documenting the world with my camera, what am I doing? Perhaps an explanation of how I became a photographer will help make it clear.

In the early 1990s I attended an exhibition of Ray Metzker’s landscapes at the Cleveland Museum of Art. The work literally took my breath away. The illusion of time disappeared in the viewing of his images and I felt completely alive.

Being artistically and spiritually naïve, I thought the proper response was to incorporate what I had seen into my sense of who I was. So I went into the woods with a camera to re-create a “Metzker Landscape,” working first with a 35 mm pentax, then a toyo 4 x 5, and eventually a deardorff 8 x10. Such folly was a form of grasping and could only end in failure.

Re-creating Metzker’s work was, of course, impossible, but I kept shooting and processing and printing because these activities themselves engaged me. Over the years, my work improved so that I eventually began to take pleasure from looking at my images. What I experienced when I saw them was not to remember Metzker’s remarkable photographs, even less to remember the subject of the particular picture I had taken. My delight (if that is the right word) came from the resuscitation of the feeling of making the photograph. Not that seeing the images made me remember standing in the river or field with all of my senses engaged, experiencing the light, handling the equipment and calculating the aperture and speed. What I experienced on viewing the images was the recreation of the feeling of being fully in the present moment—in short, of being completely alive.

This is what I seek in any work of art I view: the experience of being fully in the present moment. It is all that I hope to provoke in others through my own work.

One of my chosen media for this is the darkroom. Whether the subject of a photograph arises by means of the camera from the world around me, or without the camera from the infinite potential of the film emulsion itself doesn’t matter. What does matter is being completely alive.